How Your Gut Microbiota Tip the Scales on Weight Loss

These tiny inhabitants play an overlooked role in obesity

During our evolutionary history as a species, food shortages were common, and the ability to store energy as fat was advantageous for survival. In the modern world however, where food is easily accessible, the same behaviors that once helped us may now hamper our progress.

When we discuss metabolism, we usually only focus on our own contributions to physiological processes in our bodies. But the contribution of our microbial inhabitants is equally, if not more, important.

A sizeable body of evidence has shown that the human gut microbiota determine the effects of both diet and exercise on weight loss and metabolism.

Got Guts?

Our intestines are home to trillions of microorganisms. While most microbiome research so far has focused on bacteria, we also harbor many different types of archaea, protists, fungi, and viruses.

These microbes contribute to digestion and immunity, protect against pathogens, provide nutrients, influence our risk for chronic diseases, drive social behavior, and impact our metabolism.

Certain bacterial signatures predict body-mass index (BMI), while baseline microbiota profiles help explain why some dieters shed pounds easily and others plateau.

The Energizer Bunny in Your Gut

In 2006, Dr. Jeff Gordon’s lab began to elucidate the connection between diet, the gut microbiota, and obesity. His early research discovered that the microbiomes of obese mice are enriched in genes that allow more energy to be harvested from the diet. Studies estimate that around 10% of the calories in a typical Western diet come from these microbial conversions.

Transplanting the gut microbiota of obese mice into lean mice resulted in obesity even without an increase in food consumption. Studies have also shown that transplanting gut microbiota from obese humans into germ-free mice leads to greater weight gain and fat accumulation than transplants from lean individuals.

Phascolarctobacterium and Dialister

If you’ve ever unsuccessfully tried dieting to lose weight, your gut bacteria may be to blame. A 2018 study published in the journal Mayo Clinic Proceedings found that an individual’s microbial makeup determined the success of dieting efforts for weight loss.

Purna Kashyap, a gastroenterologist at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, tracked 26 people who were following a low-calorie diet as part of a weight loss program for three months.

“We found that people who lost at least 5 percent of their body weight had a different gut bacteria as compared to those who did not lose 5 percent of their body weight,” Kashyap explains.

Those individuals who achieved positive results on a low-calorie diet had an abundance of a bacterium called Phascolarctobacterium in their guts whereas non-responders were enriched with a bacterium called Dialister.

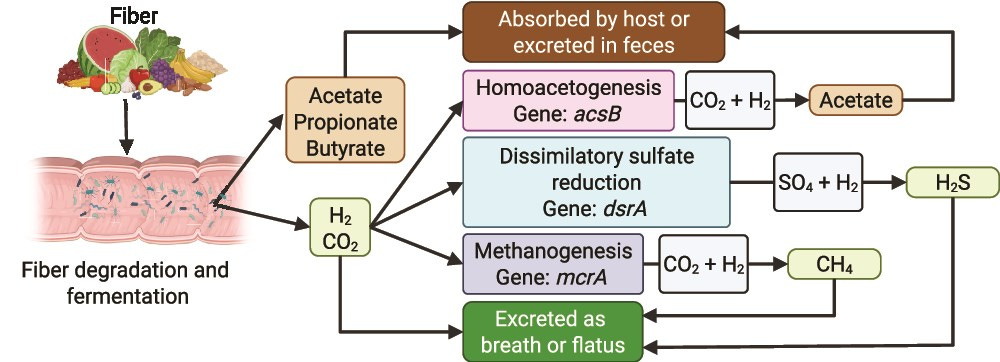

So how might different kinds of bacteria affect weight loss? A lot of food calories are absorbed courtesy of our microbiota. When we eat whole foods, nutrients are absorbed in the small intestine, and the undigested bits are converted into additional energy by our gut microbiota.

According to Martin Blaser, a professor in the Department of Microbiology at NYU Langone Medical Center,

“Somewhere between 5 to 15 percent of all our calories come from that kind of digestion, where the microbes are providing energy for us, that we couldn’t [otherwise] get.”

In times of food scarcity, the extra energy would be a boon, but in an era where most people want to lose weight, those extra calories are undesirable. “If times were bad, if we were starving, we’d really welcome it,” says Blaser.

Akkermansia

Akkermansia muciniphila, a common human gut symbiont, is over 3,000 times more prevalent in lean mice than in those genetically predisposed to obesity. When transplanted into obese mice, they lose weight and show fewer signs of type 2 diabetes.

The altered abundance of Akkermansia may even account for the success of gastric bypass surgery, an operation that reduces the size of the stomach. People often lose a substantial amount of weight post-surgery, which is normally accredited to their smaller stomachs.

But the procedure also restructures the gut microbiome and leads to a higher abundance of Akkermansia. If you transplant these restructured communities into germ-free mice, those mice start to lose weight.

Supplementing human volunteers who were overweight or obese with live or pasteurized A. muciniphila improved glucose tolerance and reduced fat mass.

Christensenellaceae

Possessing gut bacteria belonging to the Christensenellaceae family is positively correlated with having a healthy weight. While diet typically shapes the gut microbial community more than genetics, Christensenella minuta is an exception, as this species tends to be highly heritable and run in families.

In 2014, Goodrich et al. were the first to observe that Christensenellaceae were significantly enriched in individuals with a normal BMI (18.5–24.9) compared to individuals categorized as obese (BMI ≥ 30). Since then, her finding has been corroborated among many different demographic populations globally.

In fact, Christensenellaceae is associated not only with BMI but also with adiposity as measured by DEXA scans. Consistent with the leanness association, the abundance of Christensenellaceae increases after diet-induced weight loss.

A 2019 review by Jillian Waters and Ruth Ley of the Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology discussed numerous associated health benefits, including improved metabolic health, lower risk of inflammatory bowel disease, and greater longevity.

A 2021 article published in the journal Cells even described a specific strain of Christensenella minuta that could potentially be used as a live biotherapeutic for obesity!

The Future of Weight Loss Interventions

If microbes can have such a drastic effect on weight and metabolism, is a simple microbiota transplant or probiotic cocktail the cure? Can we throw out our pre-existing knowledge of the importance of diet and lifestyle? Science suggests no.

Our understanding of the microbiome complements but doesn’t completely replace our knowledge of obesity. In 2013, one of Gordon’s graduate students, Vanessa Ridaura, demonstrated the entanglement of diet and the gut microbiota.

She first transferred lean and obese microbial communities into germ-free mice and then proceeded to house both groups in the same cage. Mice frequently engage in coprophagy, the act of consuming each other’s feces, and thereby quickly acquired their neighbor’s microbes.

Ridaura noticed that microbes associated with lean people were able to readily colonize “obese” communities and arrest weight gain, but the reverse wasn’t true. Microbes associated with obesity could never establish in hosts where “lean” microbes were already present.

But the lean microbes didn’t have any distinct advantages over obese ones when it came to taking up residency in the mouse gut. Rather, Ridaura had tipped the balance in their favor by feeding her mice fiber-rich plant chow.

Microbes from lean donors were more enriched for genes that encode for fiber-degrading enzymes and therefore fared well with a plant-based diet. Feeding the mice fatty, low-fiber chow, representative of the standard western diet, swiftly put an end to the lean microbes’ reign.

No longer armed with fiber, the lean microbes were powerless to stop weight gain. A fiber-deprived diet is proverbial kryptonite for your gut microbiota. Residents of a rainforest would fare poorly if dropped into the middle of a desert.

Similarly, gut ecology is just as important as community composition and dictates what kind of microbial inhabitants can take up residence. If the research conducted so far is any indication, providing for our microscopic allies can help guard against obesity and metabolic disease.

Treating Obesity with Bugs, Not Drugs

When it comes to obesity, patients and researchers alike often have more questions than answers. How does metabolism vary among individuals? Why do some people have an easier time losing weight than others? Which factors—genetic, diet, lifestyle, environmental exposures, microbiome—exert the strongest influence over type 2 diabetes risk?

It took me about two years to get my microbiome to handle a plant-based diet without sending me to the bathroom. But once it settled down, my digestive system could handle a variety of greens, nuts, and grains with no problems. My weight is fine, not a problem. Thanks for this posting. I always learn so much from your articles, Nina. I appreciate it.