Let’s talk about stress, baby

And antifragility

Let’s talk about all the good things and the bad things

That may be

Let’s talk about stress

— My attempt at parodying a 1991 Salt-N-Pepa classic

Stress is an unavoidable part of our daily lives. How can we mitigate stress so that it doesn’t cause adverse health outcomes? How can we leverage the benefits of stress in order to help us stay motivated? Is there a sweet spot when it comes to stress exposure?

A Stressed Out Society

Last time, I briefly mentioned the stress hormone cortisol and the role it plays in appetite regulation. When we’re stressed or sleep-deprived, cortisol levels spike, increasing appetite and causing us to crave comfort foods. Unfortunately, modern society is chock-full of stressors.

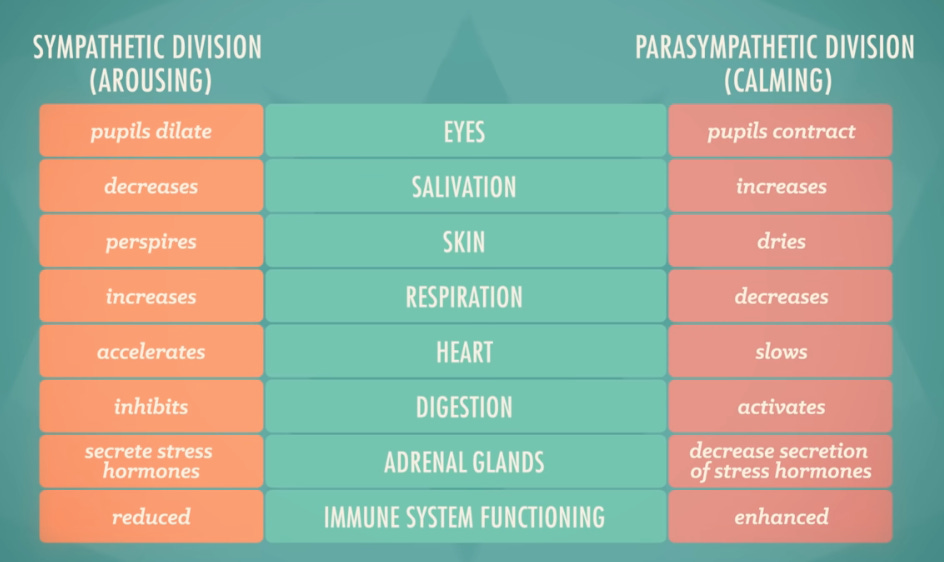

Constantly getting inundated with text messages, emails, and Slack notifications can overstimulate your “fight or flight” response, leading to chronically elevated cortisol levels. This in turn can impair proper functioning of your prefrontal cortex, the region of your brain responsible for good decision-making. Inhibition of the PFC can cause us to engage in risky behaviors like texting while driving.

Continuous engagement of your sympathetic nervous system also causes your adrenal glands to release adrenaline and norepinephrine, which speed up your heart rate and raise your blood pressure, respectively. This is why chronic stress can contribute to hypertension over time.

The autonomic nervous system in your brain communicates with the enteric nervous system in your gut, which explains how stress can lead to digestive issues. Cortisol allows for the mobilization of your muscles at the expense of “rest and digest” activities such as the normal rhythmic contractions that move food along your digestive tract. Stress can also change the composition of your gut bacteria, which can affect your digestive and overall health.

Chronic stress can dampen immunity, making you more vulnerable to infections and slowing the rate at which injuries heal. Curbing chronic stress is even essential for longevity, as high levels of stress are associated with shortened telomeres, the shoelace tip ends of chromosomes that measure a cell’s age. Telomeres allow for DNA replication and shorten with each successive cell division. When telomeres become too short, a cell can no longer divide and dies.

Mindsets About Stress

Psychologists define stress as the physical and mental response to events that we consider challenging or threatening. In other words, stress is a reaction to a disruptive stimulus, which means that the amount of stress we experience is largely dependent on how we appraise situations. When you miss a flight or someone schedules a last-minute meeting at work, you can either roll with the punches or get worked up.

Stressful situations are inevitable, but the way in which we respond is what really matters. If we view stressful situations as challenges that we can control and master rather than as threats that are insurmountable, we will perform better in the short term and stay healthier in the long run.

Stanford Psychology Professor Alia Crum describes mindsets as portals between conscious and subconscious processes. In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, she conducted an experiment in which she asked volunteers to watch videos about the nature of stress. One group didn’t watch any videos, one watched videos that detailed the debilitating side of stress, and another group watched media that emphasized the enhancing nature of stress.

The goal was to change people’s mindsets and observe the results. Crum found that just nine minutes of videos a week were enough to change people’s mindsets about stress and the incidence of physiological symptoms associated with stress like backaches, muscle tension, insomnia, and tachycardia.

People who watched the enhancing videos reported better work performance and fewer symptoms compared to the group who watched the debilitating videos. Interestingly, those in the debilitating group didn’t report a worsening of symptoms, which could be because the idea that stress is debilitating is already the dominant mindset.

The Comfort Crisis

Of course, stress isn’t all bad, and a certain amount is actually required in order to keep your bodily systems humming along at peak performance. In his book The Comfort Crisis: Embrace Discomfort To Reclaim Your Wild, Happy, Healthy Self, journalist Michael Easter argues that our calorie-rich diets, perfectly temperature-controlled environments, and relatively sheltered lives could be the reason for many modern mental and physical ailments.

Modern conveniences like fast food, air conditioning, and smartphones allow for easy access to both necessities and luxuries. Easter cites evidence from exercise scientists, economists, and spiritual leaders about the benefits of discomfort for our well-being and makes the case against sedentary activities that diminish challenge in favor of convenience such as:

choosing the elevator instead of taking the stairs

eating as a result of boredom instead of physiological hunger

spending an average of 95% of our time indoors

To push back against the latter and test his physical and mental limits, Easter embarked upon his own 33-day wilderness journey to the Alaskan backcountry. Epic outdoor challenges mimic some of the stressors our ancestors experienced and may offer more tangible health benefits than activities like organized sports.

Leaving our sterile, modern worlds and confronting new stressors can lead to improved self-esteem, character building, and psychological resilience. The well-known conservationist John Muir conveyed a similar sentiment in his writings on California’s High Sierra peaks:

Few places in this world are more dangerous than home. Fear not, therefore, to try the mountain-passes. They will kill care, save you from deadly apathy, set you free, and call forth every faculty into vigorous, enthusiastic action. Even the sick should try these so-called dangerous passes, because for every unfortunate they kill, they cure a thousand.

Transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau had an analogous idea when he decided to spend two years on the shores of Walden Pond:

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived…I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life.

Muir and Thoreau both argue that we need to shake ourselves out of apathy and complacency in order to embrace our full potentials and realize just how much we’re capable of accomplishing. Reconnecting with wilderness can benefit us in more ways than one.

Lack of exposure to natural environments can adversely affect gut microbiome diversity, the loss of which has been linked to almost all chronic diseases. The hygiene hypothesis posits that the loss of friendly ancestral bacteria could be driving our current epidemic of autoimmune diseases.

What Doesn’t Kill You…

Mark Seery, a psychologist at the University of Buffalo, has spent his life researching the edge of human comfort zones. While wading through the scientific literature, he came across a theoretical concept called “toughening,” which seemed to manifest among young squirrel monkeys that experienced transient separation from their families during early life as part of a 2004 study conducted at Stanford.

Squirrel monkeys exposed to early life stress exhibited enhanced brain development and improved cognition compared to their non-stressed peers. Seery wondered whether this same phenomenon applied to humans and decided to set up an experiment of his own to find out.

His research team recruited 2,500 everyday Americans across all ethnicities and socioeconomic backgrounds between the ages of 18 and 101. Half the participants were female; half were male. The demographic makeup of the research group resembled that of the United States.

Researchers conducted surveys to ask these people about their experiences with stressors like natural disasters, serious illness, physical assault, death of loved ones, and financial hardship. Compared to those who had lived relatively sheltered lives, people who had faced some adversity reported higher levels of life satisfaction, presented with fewer physical and psychological symptoms, and were less likely to use prescription painkillers.

Facing some challenges but not an overwhelming amount had instilled a certain degree of resilience, allowing them to better cope with new stressors. These relationships can be plotted along U-shaped curves where both very low and very high levels of cumulative lifetime adversity are associated with less favorable health outcomes.

Seery wondered if he would observe the same relationship in a controlled environment. He brought a group of undergraduate students into his lab and asked them about difficult life events and then asked them to immerse their hands in a bucket of ice water for as long as possible.

As predicted, people who endured moderate levels of lifetime adversity reported feeling less intense pain and were less likely to catastrophize or ruminate over discomfort. This finding also translates to other types of stressors like giving a difficult exam or speaking in public. People who have experienced some adversity are less likely to feel overwhelming dread and more likely to view the experience as an opportunity.

Antifragility and Hormesis

Resilience means bouncing back to the same level you were at before. But what if we could take this idea a step further and become even better than we were before? People who emerge from tragedy functioning at a higher level than before exhibit a phenomenon known as post-traumatic growth.

Social psychologist Laura King finds that some individuals who undergo incredible adversity not only display higher levels of happiness but also develop greater cognitive complexity as a result of their experiences. In contrast to post-traumatic stress disorder, post-traumatic growth is characterized by enhanced abilities and a propensity towards antifragility.

In his book Antifragile, Nassim Nicholas Taleb describes the difference between robust and antifragile systems. Robust systems can take multiple hits and keep going. Eventually they break down, but it takes more than one shock to the system. Antifragile systems, on the other hand, become stronger when stressed. Taleb writes,

Some things benefit from shocks; they thrive and grow when exposed to volatility, randomness, disorder, and stressors and love adventure, risk, and uncertainty. Yet, in spite of the ubiquity of the phenomenon, there is no word for the exact opposite of fragile. Let us call it antifragile. Antifragility is beyond resilience or robustness. The resilient resists shocks and stays the same; the antifragile gets better.

Systems such as muscle fibers and adaptive immunity can be considered antifragile since they actively adapt and require stressors for optimal function. Lifting weights causes microtears in muscle fibers, allowing muscle to grow stronger. Adaptive immunity is the reason vaccines impart protection against future infection.

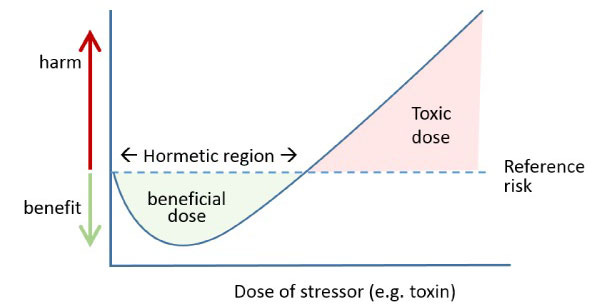

The idea of antifragility is closely related to the biological concept of hormesis. The basic premise of hormesis is that what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger, as long as the toxic exposure is in low, intermittent doses.

Hormesis exhibits a paradoxical phenomenon known as a biphasic dose response, whereby low doses produce beneficial effects but high doses produces harmful effects. In other words, the dose makes the poison. Mithridatism, the practice of developing tolerance to a poison by taking gradually larger doses of it, is a similar concept.

Within the region called the hormetic zone, the response to stressors and toxins is favorable. The threshold at which a given exposure becomes harmful varies considerably depending on the stressor and in accordance with individual biochemistry.

Low amounts of certain stressors are thought to trigger protective cell responses. For example, sunlight exposure induces double-stranded DNA breaks, which then prompt cellular repair mechanisms to also fix any previous chromosomal damage.

Hormesis is the reason that antioxidant-rich foods are considered healthy. Many plant-derived molecules, or phytochemicals, act as a defense mechanism against insects. When we consume these compounds, they cause our bodies to adapt appropriately by upregulating endogenous antioxidant production.

Dietary phytochemicals that produce hormetic effects include resveratrol found in red grapes and wine, sulforaphane found in broccoli and other cruciferous vegetables, capsaicin found in chili peppers, and various polyphenols found in green tea, turmeric, blueberries, citrus fruits, and dark chocolate.

Other examples of hormetic stressors include fasting, calorie restriction, alcohol consumption, and exposure to temperature extremes.

Episode Summary

The Stoics believed that adversity was inevitable and should be embraced. Seneca said the only people to pity are those who never experience difficulty because: “No one can ever know what you are capable of, not even you.”

The true nature of stress is paradoxical, manifold, and complex. Chronic stress can impair immunity and our ability to make good decisions, but our bodies’ inbuilt stress response can help us respond to immediate threats by narrowing our focus and speeding up the rate at which we’re able to process information.

Viewing stressors as challenges rather than threats allows your brain and body to respond more adaptively. Natural environments test our physical and mental endurance in ways that expand creativity while taming burnout and anxiety.

A certain degree of stress can enhance performance. Phytochemicals possess health-boosting properties because of their ability to upregulate our bodies’ cellular stress response. Moderate exposure to hormetic stressors can improve well-being by triggering inbuilt protective mechanisms and making us more antifragile.

I leave you with this quote from neurobiologist Rita Levi-Montalcini: “Do not fear difficult moments; the best comes from them.” Things don’t always happen for the best, but we can always choose to make the best of the things that happen.

If you’d like to support the show, feel free to share this post! Music for this episode, “New Beginnings” by Joshua Kaye, was provided courtesy of Syfonix. This episode’s audio was edited using Descript. Some links are affiliate and help support my mission to share actionable health insights with the general public at no additional cost to you. Thank you!