Why Some People Never Seem to Gain Any Weight

Hint: It’s not a fast (basal) metabolism

We all know that one person who can seemingly indulge in comfort foods to their heart’s content without gaining any weight, like your colleague Susan from accounting. While it’s tempting to blame genetics or a turbocharged metabolism, the real answer may lie in something more subtle and malleable: non-exercise activity thermogenesis, better known as NEAT.

Metabolism 101

Most of us are already familiar with how important physical activity is for our long-term health, but physical activity doesn’t just include structured, planned exercise like working out at the gym or running.

Some individuals — think fast talkers and fidgeters — move quite a bit even at rest and therefore exhibit very high NEAT, or non-exercise activity thermogenesis. Daily tasks contribute to energy expenditure in the form of NEAT, which includes activities like:

walking your dog

washing dishes

cooking & cleaning

driving

typing

vacuuming

folding laundry

gardening and yard work

pacing while talking on the phone

carrying groceries

building IKEA furniture

dancing in the shower

While many weight loss programs tout the benefits of exercise, far fewer account for the impact of this significant but often overlooked source of energy usage. Let’s go over some basics of energy metabolism:

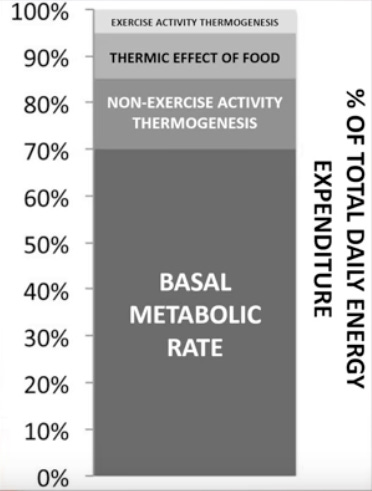

The total amount of energy we consume on a daily basis is known as total daily energy expenditure (TDEE), which is the sum of all energy used for both resting and non-resting activities.

The bulk of the energy we consume on a daily basis goes towards maintaining basal metabolic rate (BMR), or resting energy expenditure, which includes all the energy used to keep you alive.

BMR encompasses activities like vital sign regulation, breathing, blinking, sleeping, and brain function. BMR also positively correlates with lean body mass since muscle requires a considerable amount of energy to maintain.

Non-resting energy expenditure can be subdivided into thermic effect of food (TEF), non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT), and exercise activity thermogenesis (EAT).

Thermic effect of food (TEF), or diet-induced thermogenesis, includes energy used for digestion. Calories from protein exhibit the highest TEF, followed by calories from carbs and calories from fat.

As the name implies, exercise activity thermogenesis (EAT) involves physical activity like walking, swimming, jogging, cycling, or lifting weights.

Non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT) tends to be a greater contributor to total daily energy usage than exercise and encompasses all energy expenditure that isn’t used for sleeping, eating, or sports-like exercise. In other words, NEAT accounts for movement that isn’t structured exercise.

Total daily energy expenditure = basal metabolic rate + non-exercise activity thermogenesis + thermic effect of food + exercise activity thermogenesis

TDEE = BMR + NEAT + TEF + EAT

Since BMR is determined by lean mass and organ size, and TEF varies only with diet composition, NEAT is often the swing factor between weight-stable Susan and everyone else.

NEAT As a Component of Total Daily Energy Usage

While exercise constitutes a mere 5% of total daily energy expenditure in sedentary people (but up to ~20% with regular training), NEAT can account for up to 3x as much energy but can be significantly harder to track. In highly active people, the ratio can flip.

People who work physically demanding jobs like construction work and farming may burn up to 2,000 calories more than individuals who work desk jobs. NEAT has been shown to directly mitigate gains in fat during periods of overfeeding.

When researchers at the Mayo Clinic fed non-obese volunteers 1,000 calories in excess of daily maintenance requirements, differences in fat accrual varied 10-fold depending on varying levels of NEAT. Individuals with the highest levels of NEAT hardly gained any extra weight.

Overall, NEAT has been on the decline with the advent of modernization and urbanization. City and office environments encourage sedentary lifestyles, and video games and virtual reality have replaced outdoor activity among schoolchildren.

Increasing levels of NEAT can be as simple as taking the stairs instead of the elevator, parking further away from store entrances, or stretching while watching Netflix.

Is Sitting the New Smoking?

If most of our waking hours offer an opportunity to increase NEAT, is our current epidemic of sitting the problem? Turner Osler, a research epidemiologist at the University of Vermont, researches “sitting disease,” which he describes as

a constellation of obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease that frequently come as a package deal.

Herman Pontzer, an anthropologist at Duke University and author of Burn, has studied our evolutionary behaviors for the past 20 years and says that sitting (at least the way westerners do it) can be incredibly harmful for our health.

Hunter-gatherer groups like the Hadza of northern Tanzania spend as much time resting as people in Western countries do, but they don’t use chairs. The Hadza squat or kneel when resting, engaging their muscles in a way that reduces cardiovascular disease risk.

Even into their 70s and 80s, the Hadza maintain healthy lipid profiles, blood pressure measurements, and blood glucose levels, according to Pontzer’s data. The Hadza’s use of active resting postures may directly contribute to their long-term health.

When your muscles contract, they up-regulate an enzyme called lipoprotein lipase (LPL) in the walls of nearby blood vessels. LPL breaks circulating triglycerides into free fatty acids, which the working muscle cells can then absorb and burn for energy.

Can Standing Desks Help?

Appeals to cardiovascular disease prevention aren’t motivating enough to galvanize behavioral change, but the immediate promise of back pain relief is. Adopting active sitting postures may solve both problems simultaneously by spurring neuromuscular systems into action.

But standing desks sometimes have the opposite effect. In 2018, a group of researchers followed over 7,300 people for 12 years. Half the participants worked in sitting occupations, the other half in standing jobs. After adjusting for confounding variables, the static standing group experienced double the rate of heart attacks.

According to Osler, standing desks encourage an unfavorable posture that causes blood to pool in your extremities rather than circulate throughout your body. For this reason, standing still in an assembly line or standing guard at Buckingham Palace are probably detrimental to blood vessel health.

Think Yourself Thin?

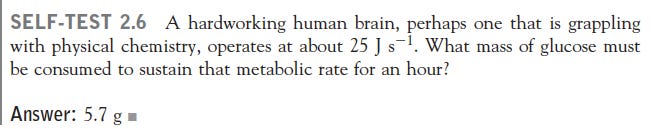

Does the mentally demanding task of trying to solve a difficult chess problem or crossword puzzle burn more energy than a lazy Sunday spent scrolling through social media? Science suggests yes.

“You will in fact burn more energy during an intense cognitive task than you would vegging out watching Oprah,” says Ewan McNay, an associate professor of psychology and behavioral neuroscience at the University of Albany.

Exhibit A: practice problem from my college physical chemistry textbook

Weighing in at just under 2% of your total body weight, your brain consumes a whopping 20% of your total energy expenditure, making it the body’s most energetically expensive organ.

Your brain prefers to use glucose for fuel and consumes a significant amount of energy to keep you alert, monitor your environment for threats, and communicate with other organs.

But McNay argues that the change in energy expenditure observed with tough mental tasks is modest as best, with only 100–200 additional calories burned for every eight hours of mentally demanding work.

The brain’s dependence on glucose requires refueling in order to keep operating at peak performance, and the additional calories consumed would likely outweigh any extra energy burned during cognitively challenging tasks.

TL; DR

Energy expenditure in the form of NEAT (non-exercise activity thermogenesis) can significantly contribute to weight loss.

NEAT can account for 200–700 calories in most adult and up to 2,000 calories of daily energy usage in heavy-labor occupations.

Daily activities such as household tasks can accelerate fat loss by contributing to NEAT.

Movement should be encouraged, and time spent sitting or standing passively should be kept to a minimum.

Compulsive leg shaking feels left out.

Loved this post! It’s one of the clearest explanations I’ve seen for the “my friend can eat anything” phenomenon without falling back on the lazy “fast metabolism” trope. From a physiology lens, your point about NEAT as the swing variable is exactly right: BMR and TEF don’t usually vary enough to explain the day-to-day gap we observe between two people with similar body size, but small, continuous movement differences absolutely can. And the Mayo overfeeding example is such a memorable anchor for how behavioral micro-movements can buffer fat gain.

I also appreciated the nuance on “sitting disease” and the Hadza contrast; not “move more” in the abstract, but how you rest matters (chair sitting vs active resting postures), because muscle contraction is a metabolic signal (LPL, TG handling, etc.), not just calorie burn.

My favorite practical takeaway: NEAT is the most malleable part of TDEE for most busy adults. So the winning strategy isn’t forcing more gym time (which people drop), it’s redesigning the day so movement becomes the default: walk calls, stairs, parking farther, “movement snacks”, and breaking up long sitting blocks.

High-signal, very actionable, and refreshingly non-moralizing!